Photo credit: Felix Marquez/AP Photo

5th August 2025

Extreme heat has become a regular feature of life in many parts of the planet, but the way it is felt depends on who you are and where you live. People with wealth and better access to infrastructure can manage high temperatures with air conditioning, shaded homes, and green surroundings. Others live in buildings that trap heat and work jobs that involve long hours outdoors. In most cases, the groups facing the greatest risk are already marginalised in other ways.

Between 2010 and 2019, the lowest-income regions experienced over 40% more heatwave exposure than the highest-income ones. And this gap is growing, driven by differences in both climate vulnerability and the ability of communities to adapt to its impacts. In poorer regions, buildings are more exposed, health systems are under strain, and power supply is unreliable. Without intervention, annual heat deaths could increase by 370% by 2050.

A recent study found that in 94% of cities in the United States (US), poorer neighbourhoods were more exposed to heat than wealthier ones. The same areas often had fewer trees, more asphalt, and buildings with poor insulation. It also found that historically redlined neighbourhoods (areas that were denied investment because of their racial composition) experience higher ambient heat than other neighbourhoods.

Some medications reduce the body’s ability to sweat, increasing the risk of dehydration and heatstroke. People with conditions like multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injuries are also more likely to experience heat-related complications. Many disabled people are not given accessible information about how to protect themselves in a heatwave, and communications often fail to account for visual, auditory, or cognitive impairments

People sleeping rough face the most direct exposure. With no roof to break the heat, and no consistent access to clean water or medical care, even short periods of high heat can become life-threatening. Even worse, their suffering is often completely ignored. In July 2024, during one of New York City’s hottest days of the summer, a journalist came across an “undomiciled woman in Chelsea weeping and screaming out begging for water, tears streaming down her face. Many pedestrians simply walked by without batting an eye until another woman stepped in and handed her a water bottle.”

People in prison, detention centres, or institutional housing also face high heat exposure, often without air conditioning or ventilation. Extreme heat in US prisons is associated with a 20% increase in violent events and a 30% increase in suicide attempts.

Even in Europe where public infrastructure is often stronger, the gaps are widening. Renters, immigrants, and women were consistently more overexposed to heat than other groups. These results held across both urban and rural areas, with rural residents sometimes faring worse due to limited access to healthcare, transport, and state support.

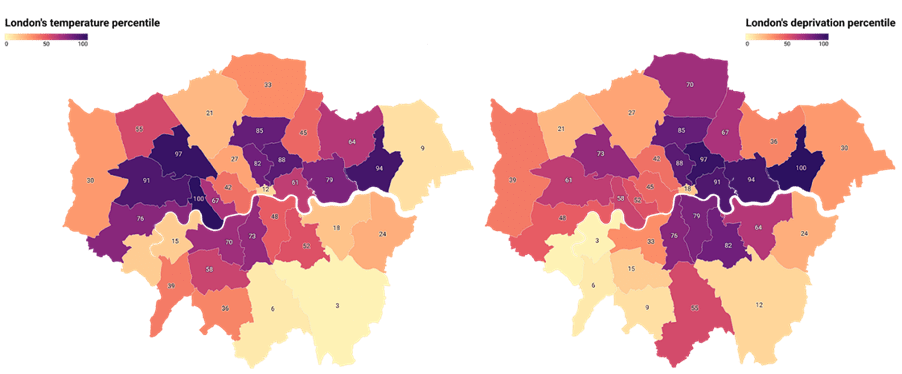

The United Kingdom (UK) is no exception. Dense urban areas like London – especially deprived neighbourhoods with little green space, suffer from being significantly warmer than rural areas. Those same areas often house the populations most vulnerable to the health effects of heat. In Greater London, ethnic minorities, children, and low-income groups live in areas with land surface temperatures up to 4°C higher than wealthier, whiter communities.

The percentiles indicate a ranking of values, with the 0th percentile being the coldest/least deprived and the 100th percentile being the warmest/most deprived.

Adapted from Frontier Economics.

Despite long-standing plans like the Heatwave Plan and the more recent Adverse Weather and Health Plan, the response has failed to prevent widespread harm. In 2023, the Climate Change Committee concluded that “progress with adaptation policy and implementation is not keeping up with the rate of increase in climate risk, and that the risks to all aspects of life in the UK have increased in the last five years”.

Workplaces have become another key terrain of struggle. As reported by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), across South Asia and West Africa, millions of workers start before sunrise to avoid the hottest hours. Others continue working through midday because they have no alternative. Most lack formal protections. Workers collapse and recover, or collapse and do not return.

Even in wealthier countries protections are thin. In Europe, regulations vary by country and are often limited to specific sectors. In the US, federal law does not guarantee breaks, shade or water for most outdoor workers. Some states have passed their own rules. Others have blocked those efforts. In all cases, enforcement remains weak.

In the UK, the Heat Strike campaign has recently called for concrete legal protections. The Heat Strike manifesto calls for a national maximum indoor working temperature of 30°C (27°C for very strenuous jobs) and a mandatory “heatwave furlough” scheme so workers get paid if conditions exceed that limit.

The World Health Organisation emphasises that many heat-related illnesses are predictable and largely preventable with proper planning. Cities need more trees, not just in parks but on every block. Housing must be retrofitted with insulation that works in both summer and winter. People need the right to stop working when conditions become dangerous.

Personal advice is no substitute. Telling people to drink more water or stay inside assumes that those options are available. It assumes people control their working hours, have access to air conditioning, and can afford higher electricity bills.

The long-term trajectory of life under extreme heat points toward widespread, societal destabilisation if adaptation remains an after-thought. By 2050, more than a billion people will face high exposure to life-threatening heat if emissions continue at current rates, with many of these individuals employed in essential but low-paid work outdoors or in uncooled environments. ILO estimates that heat stress will lead to global productivity losses equivalent to 80 million full-time jobs by 2030, concentrated in agriculture and construction, a figure they consider conservative.

The political foundations of this crisis are not hard to trace. The data on extreme weather has existed for decades – delay has not come from ignorance. Governments have deprioritised investment in adaptation in favour of economic growth and deregulated labour markets. Failure to invest in necessary protections, from enforceable labour standards to climate-resilient infrastructure, amounts to institutional abandonment. As temperatures rise, so will the urgency to challenge a system that deems some people unworthy of safety.

Written by Kevin Picado.