How Israeli companies transformed water into an instrument of settler rule and profit.

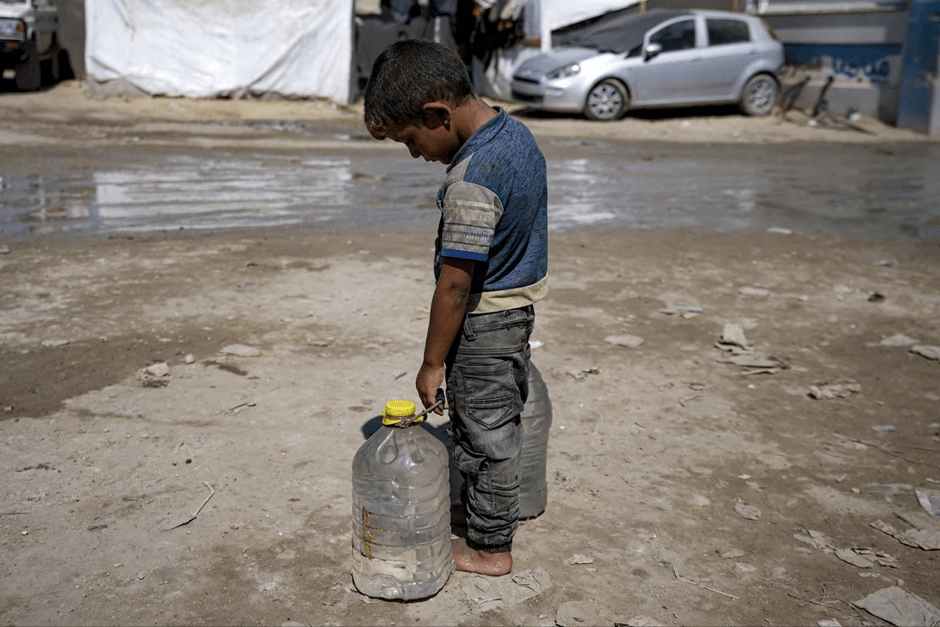

A displaced child carries filled water bottles at a makeshift tent camp in Deir al-Balah, central Gaza Strip. Photo Credit: Abdel Kareem Hana

4th February 2026

In a previous piece I examined a range of Israeli companies in the agricultural sector and their role in the Zionist settler-colonial project. Here the focus narrows to just two of them – Netafim and Mekorot, to make their role in the occupation and ongoing genocide, and the ways they profit from it on a global scale more explicit.

Founded in 1937 by the future third Prime Minister of Israel Levi Eshkol, Mekorot would go on to become Israel’s national water company, giving it the exclusive right to explore and exploit water in the area. Netafim, the biggest drip-irrigation company in the world, was established in 1965 on Kibbutz Hatzerim with backing from the Jewish National Fund and Settlement Division. The company is regularly associated with the Zionist slogan of “making the desert bloom”, a direct tie to the expansion of agricultural settlements. Eshkol himself is one of the popularisers of that myth, remarking in 1969 that:

“It was only after the Zionists “made the desert bloom” that they [the Palestinians] became interested in taking it from us.”

Two years earlier, after the end of the six-day war of 1967 he proposed leaving Palestinians without water as a strategy for driving them off their land, stating that:

“Perhaps if we don’t give them enough water they won’t have a choice, because the orchards will yellow and wither.”

Simcha Blass, one of Netafim’s founders and the inventor of drip irrigation, had earlier helped with the creation of Mekorot, later becoming the first director of the Israeli Water Department.

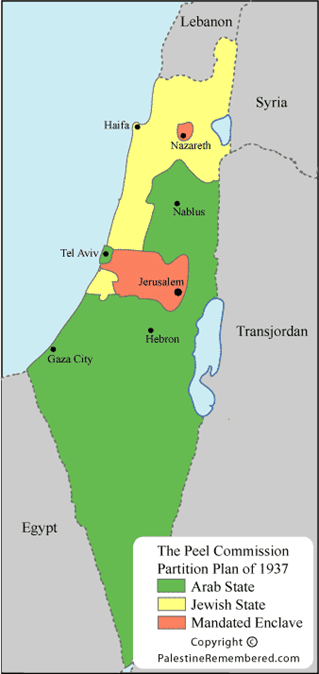

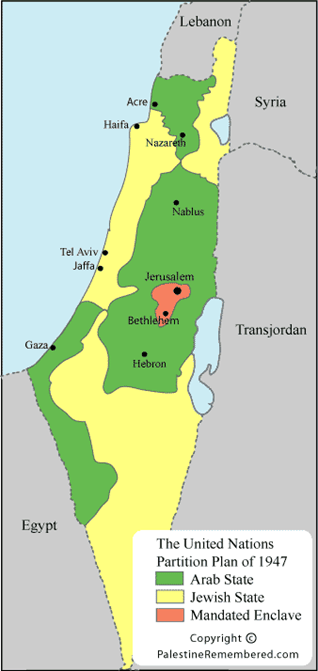

Water was central for the Zionist settler-colonial project. With the supposed over-abundance of water in Palestine becoming a discursive strategy, it implied that Palestine’s absorptive capacity could be extended to allow for an open policy of Jewish immigration, letting them expand the potential territorial state of settlers. Moreover, Blass’ unrealised dream of diverting the Jordan River to the Naqab desert (the Lowdermilk-Hays plan), played a key role in the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, as it included the whole of the Naqab desert in the settler state (unlike in the earlier partition proposed by the Peel Commission) and was explicitly influenced by the Lowdermilk-Hays plan.

After 1967 the Israeli authorities issued Military Orders 92, 158, and 291, giving them full authority over all matters relating to water. These orders forbid construction of any new water infrastructure without a permit from the Israel Defence Forces (IDF), and cancelled all water arrangements made prior to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank. Mekorot thus became the Israeli government’s executive arm for water in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

Under the (still in effect) 1995 Oslo II Accords, Israel was given control of about 80% of water reserves in the West Bank. The Palestinian supply was limited to a predetermined annual amount of 118 million cubic meters from existing drilling, 78 million from future drilling, as well as an additional 31 million sold by Israel. But despite these arrangements the West Bank only receives about 75% of the agreed amount of water, forcing the Palestinian Water Authority to buy significantly more. In 2022, the Palestinian Water Authority purchased 98.8 million cubic meters from Mekorot for both the West Bank and Gaza.

In addition to this, Mekorot charges the Palestinian Authority more per cubic meter than it charges Israeli cities. Mekorot drills up to 80% of the West Bank’s Mountain Aquifer for use inside Israel and in Israeli settlements. It built and controls virtually all the pipelines serving settlements, supplying roughly almost all of their water for domestic and farm use. Israeli military bases in the Occupied Territories also run on Mekorot water.

Virtually no permits to build water infrastructure (or any other kind of infrastructure) are granted to Palestinians. Since the year 2000, less than 4% of Palestinian building applications in Area C (the 60% of the West Bank under full Israeli control) were approved. Water wells and rain cisterns are routinely confiscated or demolished, forcing Palestinians to rely on expensive trucked water or on what little Mekorot grudgingly sells them. Israeli authorities further forbid Palestinians in Area C from collecting rainwater. By contrast, illegal Israeli settlements are fully connected to Israel’s modern water grid. Settler communities often have lush orchards irrigated year-round. In one Jordan Valley village, a local farmer recounts how he used to have:

“five, six central wells, but the Israelis took these wells from us and drained the water … All of us farmers [in Ein al-Beida] consume the same amount of water as one settler in [the illegal settlement] Mehola.”

An Amnesty International report found that during the hot season Mekorot routinely rations the supply of water to Palestinians (forcing them to buy more), while settlers get to enjoy swimming pools and large irrigated farms. The average Palestinian in the West Bank is limited to around 85 litres per day. In Gaza the situation is even worse. After 7th October 2023, the average daily water consumption per person went from 84.6 litres to only 3-15 litres (although even before October 2023, only 4% of Palestinians in Gaza had access to safe and clean water).

The national water system as depicted by the Israel Water Authority. As WhoProfits note, “the Green Line is missing on this map, which reveals that Mekorot treats Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) as one single territory. Palestinian communities in the OPT are also missing […] with only two exceptions (Ramallah and Bethlehem).”

The founders of Netafim openly linked the drip system to Zionist land politics. Netafim’s own communication hails the technology as instrumental in “making the Negev [Naqab] desert bloom.” Since 1967 the company’s products have been central to expanding Israeli agriculture onto Palestinian and Syrian lands. By equipping farms in the West Bank and the Golan Heights, Netafim actively contributes to the expansion of agricultural production by illegal settlers.

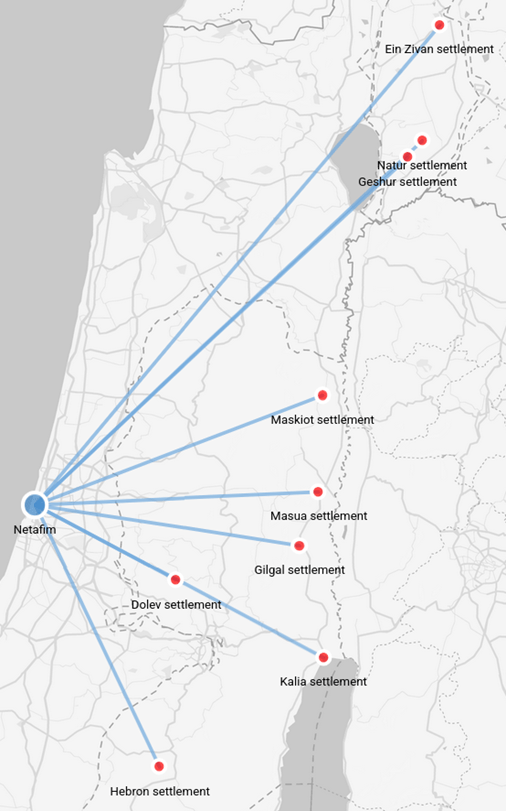

WhoProfts uncovered Netafim systems installed in Jordan Valley settlements like Masua, Kalia and Gilgal, in central West Bank settlements like Dolev, and in Golan settlements such as Geshur, Ein Zivan and Natur. Netafim has supplied, tested and refined equipment inside settlement agricultural research and development centers and experimental plots, using occupied land as a laboratory for exportable technologies and irrigation methods tailored to the settlement economy, such as water-saving regimes for seedless watermelon production and irrigation methods for Mejdool dates. Netafim also makes use of military techology. Its NetBeat digital irrigation platform was co-developed with mPrest (with the help from Amazon Web Services), a firm that adapts Israeli missile-defense software for civilian use. In fact, NetBeat uses algorithms from Israel’s Iron Dome air-defense system to optimise watering schedules. mPrest boasts of this military background, stating:

“We earned our stripes in the highly demanding defense market, having developed […] the software behind the world-renowned Iron Dome missile defense system. We soon realised that this battle-proven technology is exactly what the Industrial Internet of Things markets require for digital transformation.”

Netafim promotes this expertise as a selling point as well, highlighting its “Military technology – developed by ‘mPrest’, the creators of iron dome.”

Netafim’s presence in illegal settlements.

Mekorot effectively steals water from Palestinian farmers and exports it to settler export crops. Netafim’s drip systems then help make settler farms more profitable. In Palestinian towns like Bardala, Bani Zaid and Ein al-Beida, Mekorot drilled deep wells in the 1970s until natural springs feeding Palestinian villages ran dry. In describing the transformation, one farmer stated that “Anything that’s green is Israeli; anything that’s dry and yellow is Palestinian.”

Both companies have pursued global markets beyond Palestine, often under the banner of sustainability. For example, Netafim leads a “Better Life Farming” alliance to train smallholders in drip irrigation, marketing it as empowering poor farmers. It has also been an endorser of the UN-linked CEO Water Mandate since 2008, and the company’s Chief Sustainability Officer was invited to the CEO Water Mandate Steering Committee. These formal links give the company authoritative branding.

The framing of these companies and their technology as socially and environmentally conscious is key here. It is a rhetorical move that does two jobs: it neutralises the origin story of settler agriculture and control over Palestinian water and twists it as neutral innovations for an ailing planet. It also opens doors to public money and institutional legitimacy, so that international development banks and state subsidy schemes can be convinced to finance rollouts that look like resilience projects, rather than transfers of occupation-derived tech into new markets.

To access those markets and development funds, Netafim routes much of its business through its subsidiaries and manufacturing plants around the world, enjoying economic benefits through some of them. For example, through its Dutch subsidiary Gakon Netafim (previously known as Gakon Horticultural Projects) it can benefit from export credit guarantee schemes and tax exemption regimes. It also obtains financing through institutions like the IFC (International Finance Corporation), FMO (Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank) and other lending syndicates, which provide multi-million dollar loans to its subsidiaries around the world to mitigate risk. Meanwhile, Mekorot’s overseas projects rely on Israeli export-credit guarantees (through ASHRA) and Israeli-ministry financing (through MASHAV), essentially spreading Israeli state policy by other means.

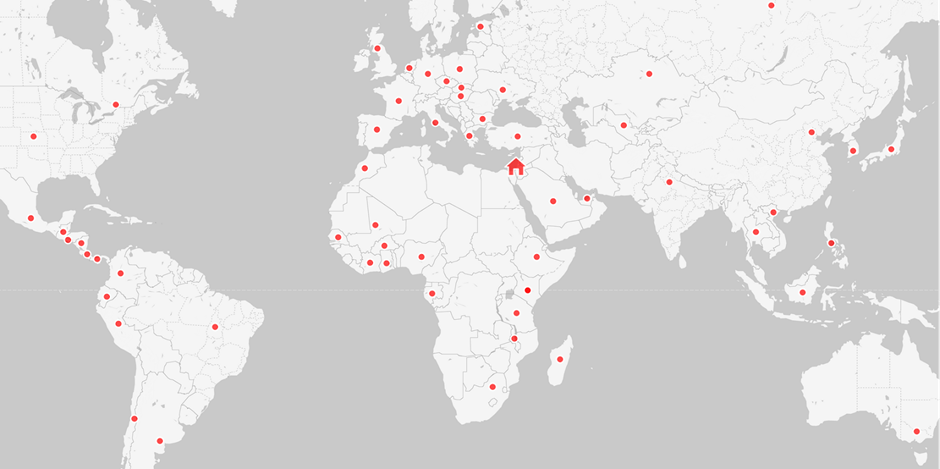

Netafim global presence.

In Latin America, the company has signed technical cooperation and master-planning agreements across Honduras, Argentina, Mexico and Chile. Reported agreements with a string of Argentine provinces position Mekorot as a designer of provincial water master plans and feasibility studies, often framed as desalination or efficiency programs. These deals are gardened through low-profile framework agreements rather than public tenders. In Mexico, Mekorot signed cooperation accords with CONAGUA on aquifer remediation and technical assistance. In Chile, Mekorot presented itself to regional governments as a partner for desalination and sustainable water management.

In Africa and West/Central Asia, Mekorot’s export strategy targets states and regional water authorities. The company has procured advisory roles with Azerbaijan’s State Water Agency, a consulting agreement with Bahrain, publicly announcing a desalination and capacity building package there after normalisation diplomacy opened Gulf markets. Mekorot has also procured a memorandum of cooperation with Morocco’s national water utility on desalination and digital water management.

Netafim’s footprint is highly visible in South Asia. The company was a component of state-run “model farming” projects in the 1990s and later entered subsidy lists and large public projects. In Tamil Nadu, they heavily profited from a subsidy scheme targeted at larger holdings and derived a large proportion of its local income from public funds. Field research shows that many farmers received expensive kits that proved ill-suited to local water quality, that sprinklers clogged under saline conditions and that promised post-installation maintenance did not materialise. In other regions contract-farming models tied to Israeli-led consortia forced production choices onto farmers and converted them into captive suppliers.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, Netafim pursues multi-stakeholder deals and public-private programs. The company partnered with the IFC and development programs in Niger to pilot climate-smart irrigation for smallholders. They also signed a reported $14 million contract with Tanzania’s Bakhresa Group to irrigate sugarcane and has active projects or partnerships in countries across East and West Africa. Those projects draw on claims to exportable Israeli Research and Development, and Netafim positions them as important for climate resilience.

For both companies the mechanism of impact is the same: to convert technical capacity into a policy package, and normalise a governance regime that privileges commercial extraction and private investment over locally governed, commons-based alternatives. They are agents of a single program connecting genocide in Palestine to profit abroad. Any serious challenge to this system starts by refusing this logic altogether and insisting that the substrate of life belongs to the collective, not to money-hungry politicians and financiers willing to make a quick buck on the back of dead men, women and children.

Written by Kevin Picado