Photo Credit: Josep Lago

13th October 2025

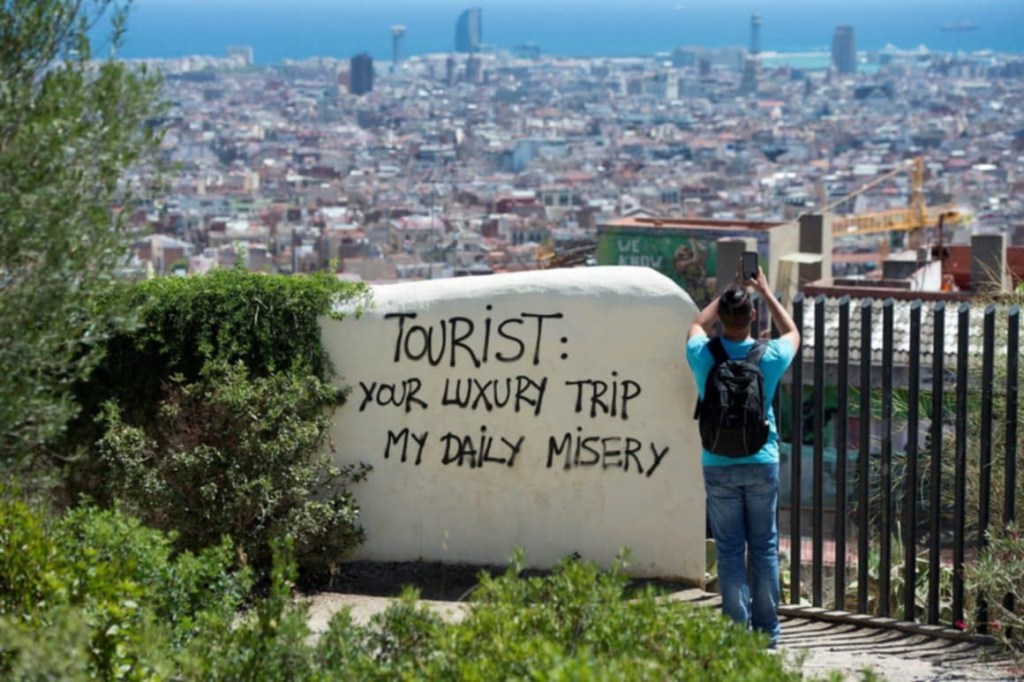

What looks like prosperity to outsiders frequently doubles as slowing disappearing neighbourhoods and ecological degradation for the locals. When visitors arrive in large numbers, the pressure on housing and services alters everyday arrangements. Long-term units are frequently converted to visitor accommodation for platforms like Airbnb, many residents lose the capacity to remain, and decisions about place tilt toward those who profit from short-term stays. The change rarely occurs as a single event. It advances through incremental zoning shifts and rising land valuations. Barcelona is a very well documented case-study on how these mechanisms operate. The city recorded roughly 15.6 million overnight visitors in 2023, and over the past decade rents and purchase prices have climbed to levels local groups associate with the expansion of short-term letting and tourist-focused investment.

Tourism often begins as an economic strategy where other forms of investment are scarce, and at first it creates visible income streams for local workers and businesses. As demand grows, the built environment adapts to serve those flows. In resort corridors, infrastructure is upgraded to improve access for higher-paying visitors, and commercial spaces reprice around quick consumption. Several popular districts in Bali, for example, reported house-price inflation has outpaced wage growth by a wide margin, producing year-on-year increases that place ordinary hospitality incomes far below the threshold needed to buy or rent near places of work. This has forced locals to opt for long work commutes (since tourism employs the majority of residents) from more affordable areas or to leave altogether.

Urban centres that cultivate cultural appeal create a mixed form of this transformation. In Mexico City the stock of short-term rentals expanded into the tens of thousands, clustering in centrally located boroughs and contributing to housing inflation that sometimes exceeds national averages. In New Orleans thousands of whole-home listings concentrate in historic wards and correlate with increased eviction pressure and a shrinking long-term rental inventory. Cape Town’s short-term rental market reached counts in the tens of thousands as well, with whole-unit listings dominating the platform economy, with neighbourhoods such as Bo-Kaap and other central districts reporting record sales and conversions, leading to high levels of gentrification.

The environmental pressures of tourism can also have a detrimental impact on working class communities. Destinations with fragile water systems or constrained energy grids have to confront rising demand as visitor numbers climb. The carbon cost of travel increases ecological stress where landscapes and climates are part of the attraction. Investors then target places deemed climatically desirable, bidding up land in areas already constrained by infrastructure. In Puerto Rico, listing prices in parts of its capital have climbed to levels far above typical household incomes, leaving many residents with fewer feasible housing options precisely as storms and other shocks remain a persistent threat.

Public authorities often prioritise real estate projects over residents’ needs, directing infrastructure and regulatory decisions in ways that raise land value for developers while eroding communal access and environmental safeguards. In Costa Rica (where I’m from), official interpretations of concession rules for the popular Papagayo area have been used to justify clearing up to thirty percent of forested land for construction of new luxury hotels, directly conflicting with forest law. Those who oppose these practices encounter legal and financial pressure that discourages dissent. A recent lawsuit against an environmental defender led to a (granted) request to seize up to forty thousand dollars in assets, bank accounts, wages, and credit cards in an attempt to silence criticism.

Policy responses to these problems often emphasise surface fixes. Capping visitor numbers can reduce congestion for a season, and tighter rules for short-term rental platforms can slow the conversion of housing into nightly lets. Yet these rarely hold when property and planning regimes still treat housing as an asset class for speculative use.

Regulation and institutional redesign offer a more durable alternative. Securing tenure through stronger rental protections and limits on residential conversion reduces the immediate risk that homes will disappear into the tourist market. Requiring registration and occupancy controls for visitor units produces entry points for enforcement and planning. Dedicating a portion of tourism taxation to public or cooperative housing redirects visitor-generated revenue into long-term assets for residents. Alternative housing models, including co-housing and community land trusts, spread costs and lower individual ecological footprints while preserving access.

Implementation is political as much as it is technical. Markets will reallocate access unless countervailing forms of power protect the local population. Community participation in planning and legal safeguards for long-term occupancy must be taken as prerequisites for any outcome that can be described as fair.

If policy instruments prioritise resident well-being and ecological limits, tourism can be reorganised to support livelihoods and community life. In the absence of such governance, tourist demand will eventually hollow out local economies and convert living places into curated displays for outsiders.

Written by Kevin Picado