Photo Credit: Basile Barjon/Stay Grounded

18th July 2025

Aviation’s climate impact is far greater than most people realise. Air travel is the most carbon-intensive mode of transport, responsible for roughly 4% of global warming (once non-CO₂ effects are taken into account). This footprint is not only large but growing rapidly. In the five years before the pandemic, aviation emissions grew around 5% annually, and after a brief COVID-19 drop, air traffic has already rebounded sharply. What is more, the International Energy Agency expects demand to grow rapidly through 2030, putting aviation on a collision course with global climate goals.

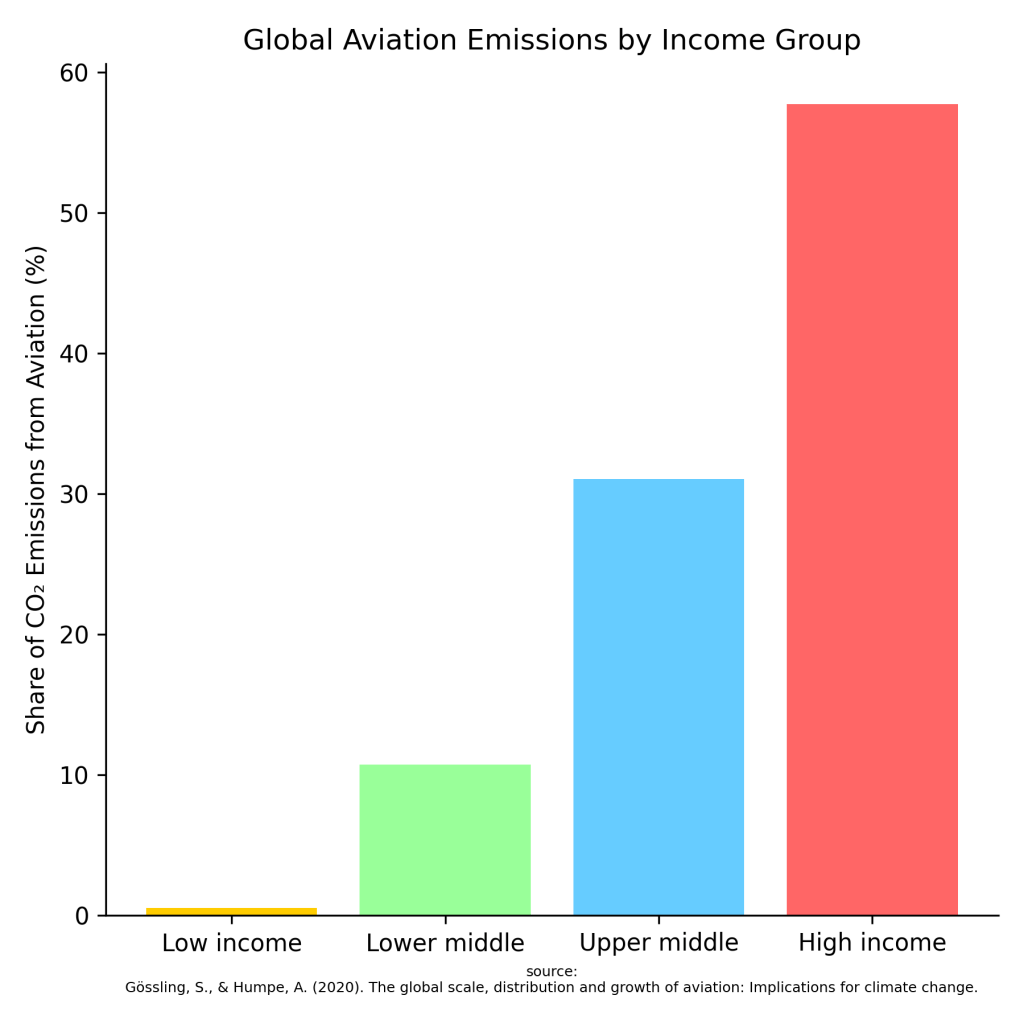

Yet the vast majority of people rarely or never fly. Only about 11% of the world’s population traveled by air in 2018, and just 1% (the frequent fliers) accounted for roughly half of all aviation emissions.

Air travel inequality exists within countries as well. In the UK, over half the population do not fly in a year, while a small minority of frequent flyers take most of the flights.

Private jets take these emissions inequalities to the extreme. They are the most energy-intensive form of flying, largely unregulated, and their emissions are exploding. Between 2019-2023, emissions increased by 46%. Nearly half of all private flights cover distances of less than 500 km, and many are linked to leisure and prestige events. Unsurprisingly, most of the people using them are located in the Global North, with the US accounting for a whopping 67% of all private flights, followed by Europe with 16.5%.

But this is not only an issue of individual excess, it is a structural problem. The aviation industry is involved in national development agendas, prestige politics and military infrastructure. Governments often act not just as regulators but also as sponsors, investors and consumers of aviation services, leading to what some academics call aviation exceptionalism.

This can be easily seen in the fact that international aviation emissions are not included in countries’ national climate targets under the Paris Agreement, and are instead regulated by the International Civil Aviation Organisation, which has delayed even its weakest commitments. Domestic aviation is technically included in national climate plans, but is often politically shielded. Only a handful of countries apply meaningful taxes or caps on aviation fuel or emissions. The European Union’s Emissions Trading System excludes most long-haul flights, and attempts to extend carbon pricing have been repeatedly watered down under industry and diplomatic pressure.

Instead, the aviation industry has continued to promote technological solutions as the main path forward. But these supposed fixes are nowhere near scale. Sustainable aviation fuels currently supply less than 0.5% of jet fuel demand and face serious limitations in terms of feedstock, land use, and cost. Hydrogen and electric aircraft remain decades away from commercial viability for anything beyond short-haul flights. Even optimistic scenarios don’t foresee any of these technologies scaling up fast enough to offset aviation’s growth.

And so, the only effective short-to-mid-term strategy to shrink aviation’s footprint is to fly less. This is an idea often dismissed as unrealistic or even framed as elitist. In truth, the real elitism is ignoring the impact of luxury travel. Given that the benefits of flying are so unevenly distributed, the only option compatible with climate justice is demand reduction, rather than forcing sacrifices on those who never fly at all.

Governments have so far shied away from taking steps to reduce how much people use or consume. Aviation still enjoys generous tax exemptions (international jet fuel is untaxed), and many countries exempt airline tickets from VAT, effectively subsidising frequent flyers. In the European Union alone, such tax breaks are estimated to reach €47 billion this year.

Avoiding the worst-case scenarios for climate change demands a different approach. This means introducing frequent-flyer levies, ending fuel tax exemptions, banning private jets where alternatives exist, and investing heavily in low-carbon transportation for all, such as trains. The failure to act on this front is not due to lack of knowledge or options, it is a failure of political will. Continuing to pretend that aviation can decarbonise while growing unchecked is nothing short of a dangerous delusion.

Written by Kevin Picado.